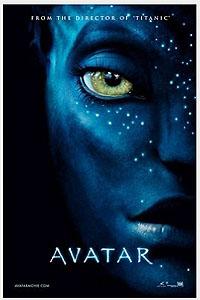

James Cameron’s Avatar: the most immersive and visually compelling SF movie ever made, but after its stunning first act, little more than a hackneyed remake of Dances With Wolves. (And like DWW, simultaneously anti-colonialist and a classic eye-rolling example of what James Nicoll calls the What These People Need Is A Honky subgenre.) That at least seems to be the evolving conventional wisdom.

I’m not saying that wisdom is wrong, exactly. When I walked out I had the same reaction that I did to Titanic: while Cameron may well be the greatest director alive, somewhere along the way his writing chops went walkabout. I stand by that. But I also hereby suggest that there is more going on on Pandora than meets the 3-D glasses, and that Avatar is not the movie that most people seem to think it is.

On one level Avatar is about a greedy, industrialized technological society that strip-mines and bulldozes vs. an enlightened pastoral society that is One With Nature and its fierce beauty. That’s true. But on another, it is nothing less than an SF movie about SF itself. Specifically, it is a visceral dramatization of the conflict between fantasy and science fiction.

Look at the visual tropes on either side. We begin in a zero-G environment, in a starship almost visually identical to that of 2001: A Space Odyssey, the high-water mark of cinematic science fiction. Attached to it are recognizable space shuttles, code for the science fiction future is now to anyone who lived through the 80s. There are battle mechs, gunships, transparent tablet computers festooned with medical imagery, cryogenic space travel. The humans are Science Fiction.

But when we get into Pandora proper, what do we find? Pointy-eared deadly archers in harmony with nature who live in trees. Maybe that says Native Americans to many, but to me (and anyone who’s read Tolkien) it also screams elves! Elves who ride dragons, no less—through the fantasyland Floating Mountains of Pandora, the existence of which is never rationalized—and who commune with the dead spirits of the elders through their World-Tree. The Na’vi are clearly Fantasy.

Avatar‘s story, then, is about the battle between fantasy and science fiction, and the ultimate triumph of fantasy. That’s what justifies its literal deus ex machina ending. (Not much else would.) Science fiction has every advantage, but fantasy wins because ultimately it is numinous, and has incomprehensible powers on its side.

Science fiction is about the known and the possible, a world that grows from our own imperfect present. Here it grows into a “grim meathook future,” as Charles Stross would say, in which Earth is constantly at war, severed spines can only be repaired for those who can afford it, and beauty must be killdozed for the sake of unobtainium. (Unobtainium! C’mon, people, how obvious a hint do you want?)

Beauty, discovery, exploration, wonder—those are mere adjuncts to this science fiction future, means rather than ends, and ultimately irrelevant compared to the conquest of all that is known. But fantasy, like storytelling itself, is about beauty and emotion and wonder; and because fantasy is numinous and unknowable, its sense of wonder is unquenchable. That’s why it must ultimately win, whether in Avatar or on bookstore shelves.

At the end of the film one character actually transforms from human to Na’vi—in other words, moves from the world of science fiction to that of fantasy. Why is this the obvious Hollywood ending? Why does it please the crowd? In part because historically, science fiction tends towards dystopia, and fantasy towards utopia; in part because the joys of fantasy are more obvious than the joys of science fiction (riding a dragon may not be easier than building a starship, but it’s certainly simpler); but ultimately, I think it’s because most of us yearn for the numinous, for the all-powerful and ultimately incomprehensible, whether it be in a church, a mosque, or projected in 3-D upon the silver screen.

Jon Evans is the author of several international thrillers, including Dark Places and Invisible Armies, and the forthcoming Vertigo graphic novel The Executor. He also occasionally pretends to be a swashbuckling international journalist. His epic fantasy squirrel novel Beasts of New York is freely available online under a Creative Commons license.